Back to the Buster Stars Interviews

Back to the Buster Stars Interviews

Ron Clark - Writer 1960 to 1974

Ron “Nobby” Clark was born in Battersea in 1923. His Great-grandfather was said to have leant money to the man who set up Coleman’s Mustard Factories! His Dad was a sniper with the Royal Welsh Fusilliers in the 1st World War whilst his Mum worked for the Red Cross. They met when his father was convalescing in Deal.

Ron first started drawing pictures for his History Master at Oakwood Secondary School. The headmaster there spotted that Ron had talent, and he was sent off to Willesden Technical College.

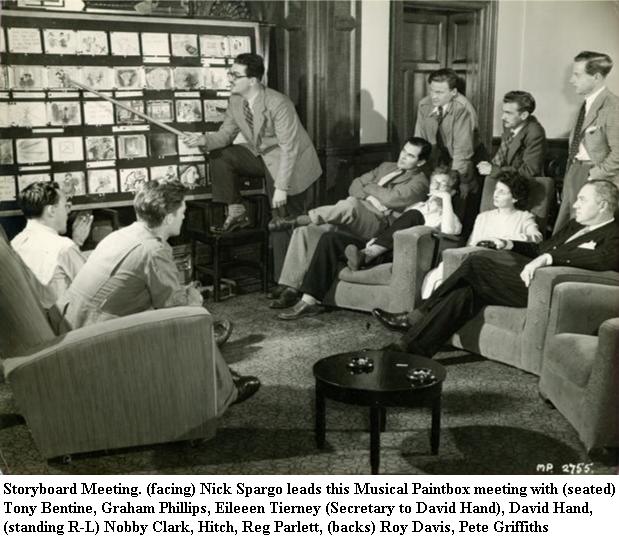

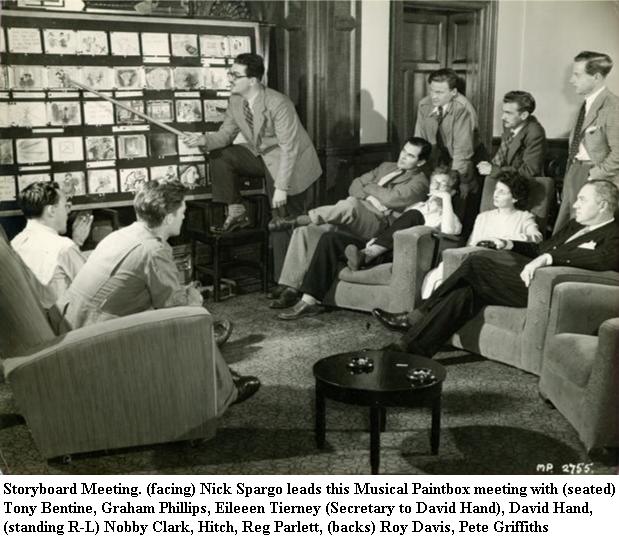

After a stint in the Air Force during World War II (in which he ended up seeing no enemy action – despite his best efforts!) he was unsure what to do next. A friend pointed him in the direction of an advert for animators at GB Animation in Cookham where he was to meet future Fleetway stars Reg Parlett & Roy Davis, amongst others.

Post Buster, he found himself writing the storyboards for Asterix with Ginger Gibbon.

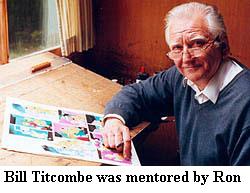

Speaking to his son, Chris before his death in 2009, Ron recalls the origins of Buster and travelling abroad becoming friends with an artist called Nadal and being the mentor of Bill Titcombe....

David Hand [the man in charge of GB Animation] said I’ll never make an animator, but he said we can use you in the story department. And I have an idea the bloke I took over from was Bob Monkhouse.

David Hand [the man in charge of GB Animation] said I’ll never make an animator, but he said we can use you in the story department. And I have an idea the bloke I took over from was Bob Monkhouse.

So what happened there?

You did a story and when you thought you’d got something you told Ralph Wright, or somebody, and he’d gather all the Herberts around, and then they’d tear it apart. You were lucky if you came out with one picture left on that bloody board. They did it on purpose, ‘what a load of old rubbish’, you know! They were doing the cuckoo when I first went, and I thought [up] a polecat, I don’t know why. I drew some polecats, or what I thought a polecat looked like anyway. The gag I started with, you’d see this thing sort of lurking about all over the place in the wood, and there was a commentary over the top of it, you see – and the commentator says ‘And of course the polecat’s extinct’ and the polecat turns around and says ‘Who stinked?’ and this was it, you started off, he’s bad tempered. This caught Ralph Wright’s eye and he shrieked with laughter [Imitates American laughter] Oh, Jesus! And he said, do this film next. But we wont’ have a polecat, he says, we’ll have an ordinary tomcat and I had to do cat gags for a long time. This is how I got to know Jack Stokes, he was animating then, he’d just started, and they had the cat thing, the usual nonsense, boy cat meets girl cat and horrible cat comes along so there’s a punch up and all the rest of it, and what they did when they were little kittens, tearing down the curtains and all the rest of it. And if you got a story accepted, you got an extra pound a week.

What was the point of all this? What were you producing stuff for? Was it for Cinema? Television was too young then.

This was for cinema, but you see the trouble was J Arthur Rank thought they could break into the American market with these things, which they could have done, I should think, but the Yanks weren’t having it. Now at the time they also had a charm school for actresses they wanted … for the films. One of the two had got to go, so of course it was the cartoon films. Which was a big mistake because the actresses weren’t much bloody good and I was one of the very last to leave. For some reason or other Dave Hand held on to me – he said ‘You’re not going yet’. I watched half the others disappear, and I watched half the curtains disappear too, and the animation desks and things like that. These blokes used to come in and raid it, Jack Stokes and so forth!

Why?

Well, they wanted the light boxes for themselves, to take home. So I was practically one of the last to leave there.

What years are we talking about here, then?

This is in 1949, 1950.

They had to finish off what they were doing. [Eventually,] Reg Parlett said to me ‘Try the Amalgamated Press’. Reg Parlett had been there for years. I knew I didn’t stand a chance on my own, like, I hadn’t got the patience to sit and draw. This is what Dave Hand said to me, you know – ‘You’ll never make an animator – your mind’s going straight onto something else’. And so I spoke to Eric Bradbury, [Chris’] other godfather.

He’d been at Moor Hall as well?

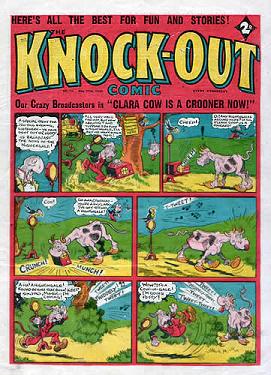

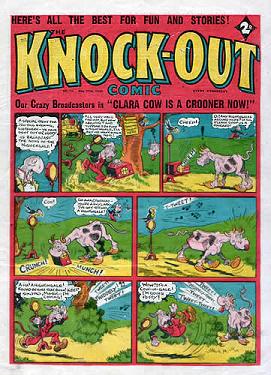

Oh, yeah, Eric was at Moor Hall. Anyway, Eric and I went along to Amalgamated Press and the only comics either of us knew were Comic Cuts, we didn’t know anything about Knockout or any of the others, so when we went there the doorman asked what we wanted and we said we wanted to see the editor of Comic Cuts, Arthur Bouchier.

Well, Arthur said, ‘We don’t deal with the ones from Cookham and that’, he said, ‘the person you see is Leonard Matthews. We had to go upstairs and he welcomed us with open arms, you know! There’s a whole bunch of you coming up here, Ron Smith, Hargreaves… he said, I’ll give you some work. And I just told him I’m getting married in two or three weeks time. That’s alright, he said, I’ll give you double pay that week as long as you put a job in. So we got work, Eric and I and just to hedge our bets we also went to D C Thompson’s, and Thompson said ‘yes, we’ll take some work from you, probably’. But we thought we’d get on with the Amalgamated Press one first to see how we got on with that.

Well, Arthur said, ‘We don’t deal with the ones from Cookham and that’, he said, ‘the person you see is Leonard Matthews. We had to go upstairs and he welcomed us with open arms, you know! There’s a whole bunch of you coming up here, Ron Smith, Hargreaves… he said, I’ll give you some work. And I just told him I’m getting married in two or three weeks time. That’s alright, he said, I’ll give you double pay that week as long as you put a job in. So we got work, Eric and I and just to hedge our bets we also went to D C Thompson’s, and Thompson said ‘yes, we’ll take some work from you, probably’. But we thought we’d get on with the Amalgamated Press one first to see how we got on with that.

When I came back from honeymoon, Matthews called me in and said the boss man, Monty Hayden wants you on the inside. So I said what happens to Bradbury? I’m not leaving him out. He said, we can come to an agreement; Bradbury can have as much work as he wants but he won’t be working with you.

So, Eric was working freelance and I was sort of stuck in the office, as was a bloke called Jim Higgins and then, blow me, Roy Davis appears, and he got taken on too.

You were both working on Knockout.

We were working on all sorts of things by then. I started, with Arthur Perceval, we started a new comic, they said they wanted a new comic. Arthur and I had a try, you know, keep working out something, and Matthews got wind of this and he hauled me in, you know – ‘Where’s your comic, that you’re doing with Arthur Bouchier?’ So I said, ‘Do you want it?’ ‘I don’t’, he said, ‘His Nibs does’, Monty Hayden, you know, he wants lots more [indecipherable]. Of course, they’d got this Daily Mirror bunch came over, you see, and he said they wanted the comic and they wanted it called ‘Buster’.

So a lot of what we put into what we were going to do, Arthur and I, that went in to Buster. So I said, ‘Is Arthur going to do it?’ ‘Oh, no, no – he’s going to do something else’. And I got shot out to Spain to pick up Spanish artists.

Matthews sent me over there with Barry Coker and Keith Davies. And we went to Barcelona first and we met the Spanish artists, the Barcelona ones – there was Angel [Nadal], Rafart, Jordi Gin – a lovely bloke,

Then we went down to Valencia and we met some others down there and I had to collect all their artwork to bring back. Angel wouldn’t part with his unless someone forked out some money first. The others did, they just handed them over. Not Angel.

Anyway, I came back and when we got back Matthews had a look and said ‘Yes, good, that’s good – we’ll have him, Angel’. I thought he’d go for Jordi Gin, or somebody like that, or Rafart. Well, we did use Rafart, but he wanted Angel and he wanted him over here.

Anyway, I came back and when we got back Matthews had a look and said ‘Yes, good, that’s good – we’ll have him, Angel’. I thought he’d go for Jordi Gin, or somebody like that, or Rafart. Well, we did use Rafart, but he wanted Angel and he wanted him over here.

So they got Angel over here and I saw him once in a bloody great ‘pew’ on his own, sitting there, so I just said hello, but I don’t think he remembered me. But then Barry came in one day and said to me: are you doing anything this weekend? He said, we nearly lost Nadal, he nearly got run over: he’s not safe to be on the streets of London, and I’m not around this weekend and I don’t know what to do with him. I said, you want me to take him home.

So I brought him home. It was funny on the train. There were two of the blokes from Horsham, there was Sid Seltzer, now he could speak French, and there was Jimmy Harvey, they were on the train together and I introduced Angel. He doesn’t speak English, but does he speak French? Try him. ‘Parlez-vous francais’ he says and Angel says ‘Oui, oui’ and off they got talking. And of course Jim didn’t stay out for long and says, is he a Catholic? I don’t know, I said, I suppose he is. Ask him if he wants to come to church. So he asked Sid to ask him if wanted to go to church. I thought Angel was going to get out of the train – Non, non, non, non! So, we got him home and the best day’s work was to take him down to Portsmouth. I didn’t realise he’d been in the navy. When we were down in Portsmouth, I thought now we’ve done it.

No, I remember it extremely well, because it was my birthday [May 26th] and you brought back a new engine for my railway train set. I must have been seven or eight. I remember it being very warm and we went to Portsmouth, went on the Victory and I suppose to Southsea. And we took him to Chanctonbury Ring on the Sunday and the only two words of English he knew were ‘No understand’.

No understand.

He always says it made a huge impression on him, just that gesture, taking him into your home. Because he would never have known, stuck in the middle of London, what it was like living in the countryside with a family.

He was a very good friend, Angel. But Rafart, he was a funny bloke, so quiet, yet his drawing was terrific, I thought. Jordi Gin was the opposite – hey-hey; I enjoyed them. But my name was mud with the British artists.

Really?

Yeah, for a long time.

For letting them in?

Yeah.

You were only doing what you were asked to do.

Yep, and I told them. I was paid go out there and get some and I found some.

That’s business, isn’t it? You wouldn’t bat an eyelid about it now; in fact you wouldn’t be able to with the European Community and so on. Lots of prejudice in the fifties and sixties still, war still not a distant memory, so they would jar at it, I suppose. I hadn’t though of it that way, actually.

They had the Cartoonist Club, which I walked out on because it was more like a sort of self-interested – ‘Look at me’ group. They had a meeting down in Bognor.

In Butlins

Butlins, yeah! Roy Davies had gone down there with his family and I was supposed to go down because they were arguing about the foreign artists then, you see. I was supposed to go down and back up the foreign artists, which I did. And I told them straight, you know: they’re as good as you; they’ve got to live.

Your closer mates presumably stood by you on that, did they? Roy Davies and the like.

Oh, Roy didn’t care.

Of course another person we haven’t mentioned is Bill Titcombe.

Yes we should get to him as part of your ‘team’. So we’ve got Arthur Bouchier your Editor, you and Roy as a little team and then Bill comes in, right?

Yes we should get to him as part of your ‘team’. So we’ve got Arthur Bouchier your Editor, you and Roy as a little team and then Bill comes in, right?

This is what I’m trying to dig into my grandson, Alex. When I first met Bill he was the office boy sort of thing, clearing up and all the rest of it and he wanted to do some cartoons. I said, go ahead; let’s see what you can do. Well, what he turned up, no way, Bill, you can’t put those in like that, you’ll have every kid in the country sending things, you know. I said, draw a motorcar like a motorcar, put four wheels on it, a bit of perspective. And he thought for a bit, I suppose and toddled off. Then he got better and better.

He was just a teenager then, wasn’t he?

Oh yes, about sixteen or seventeen. Suddenly he clicked and he never looked back. And he always swears I’m his mentor but I don’t see why.

Well he always told me that. You may not have had to explain everything but you make them see something that they haven’t seen for themselves, and that’s mentoring.

I don’t know whether Alex has got it in him, but Bill went just like that overnight sort of thing and as I say, he hasn’t looked back.

All in all, you know, I think I haven’t done anything marvellous: I could have done a lot more if I’d used my loaf a bit.

* * *

You did plenty Ron, and this is just a tiny section of your fantastic story. My huge thanks to Chris and the Clark family for sharing this with the site.

Back to the Buster Stars Interviews

David Hand [the man in charge of GB Animation] said I’ll never make an animator, but he said we can use you in the story department. And I have an idea the bloke I took over from was Bob Monkhouse.

David Hand [the man in charge of GB Animation] said I’ll never make an animator, but he said we can use you in the story department. And I have an idea the bloke I took over from was Bob Monkhouse. Well, Arthur said, ‘We don’t deal with the ones from Cookham and that’, he said, ‘the person you see is Leonard Matthews. We had to go upstairs and he welcomed us with open arms, you know! There’s a whole bunch of you coming up here, Ron Smith, Hargreaves… he said, I’ll give you some work. And I just told him I’m getting married in two or three weeks time. That’s alright, he said, I’ll give you double pay that week as long as you put a job in. So we got work, Eric and I and just to hedge our bets we also went to D C Thompson’s, and Thompson said ‘yes, we’ll take some work from you, probably’. But we thought we’d get on with the Amalgamated Press one first to see how we got on with that.

Well, Arthur said, ‘We don’t deal with the ones from Cookham and that’, he said, ‘the person you see is Leonard Matthews. We had to go upstairs and he welcomed us with open arms, you know! There’s a whole bunch of you coming up here, Ron Smith, Hargreaves… he said, I’ll give you some work. And I just told him I’m getting married in two or three weeks time. That’s alright, he said, I’ll give you double pay that week as long as you put a job in. So we got work, Eric and I and just to hedge our bets we also went to D C Thompson’s, and Thompson said ‘yes, we’ll take some work from you, probably’. But we thought we’d get on with the Amalgamated Press one first to see how we got on with that. Anyway, I came back and when we got back Matthews had a look and said ‘Yes, good, that’s good – we’ll have him, Angel’. I thought he’d go for Jordi Gin, or somebody like that, or Rafart. Well, we did use Rafart, but he wanted Angel and he wanted him over here.

Anyway, I came back and when we got back Matthews had a look and said ‘Yes, good, that’s good – we’ll have him, Angel’. I thought he’d go for Jordi Gin, or somebody like that, or Rafart. Well, we did use Rafart, but he wanted Angel and he wanted him over here.  Yes we should get to him as part of your ‘team’. So we’ve got Arthur Bouchier your Editor, you and Roy as a little team and then Bill comes in, right?

Yes we should get to him as part of your ‘team’. So we’ve got Arthur Bouchier your Editor, you and Roy as a little team and then Bill comes in, right?